Evolution of the Backsaw

When did the backsaw first appear? This is a question that at first sight, it would appear to be simple to answer. Not so. I imagined that I would just refer to the available literature for answers. It is a curious and sparsely researched area of Archaeology, plenty of material relating to axes, hammers and so on, going all the way back to the stone age. If you want to know about stone axes, there is an abundance of material. But saws seem to have slipped mostly below the radar. Saws go back to the early Egyptians who had hardened copper pull saws as early as 4900BC, but I am going to focus here on just backsaws. (A complete history of the saw would be a much more ambitious undertaking).

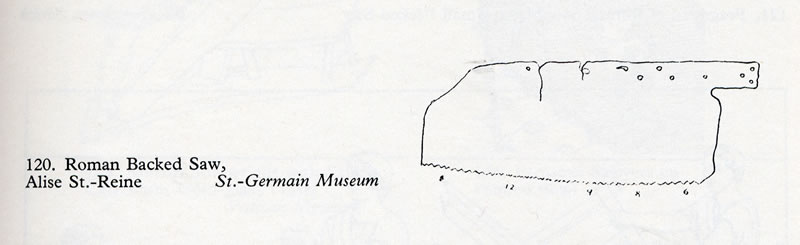

The earliest possible candidate which may have been a backsaw, is a Roman saw found at Mont Auxois, a Gaulish camp, this saw is in the museum at St.-Germain.

W.L.Goodman "A History of Woodworking Tools" pp117

The author suggests that this may have been a backsaw, because of the row of holes along the back of the blade look as if a wooden stiffening rib could have been attached, also it looks as though the handle was attached with rivets, rather than a tanged handle, he also points out that the teeth are progressive in pitch, that is closer at the toe, and wider spaced at the heel. So the earliest backsaw was progessive pitch (this saw is obviously the Lie Nielsen of the Roman world!). Nothing is ever entirely new apparently.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, the handsaw seems to pretty much dissapear from history, the Bayeaux Tapestries which illustrate the process of ship building from felling trees to launching the ships shows not a single saw. All work is done with axes, adzes and other tools.

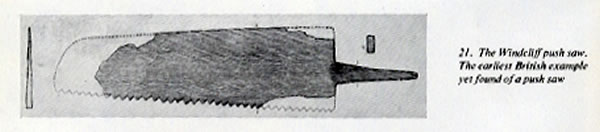

I suspect that the handsaw was still in there somewhere, hiding, in the medieval toolbox, maybe only dusted off for special jobs that couldn't be handled by the bow-saw or frame-saw. The only evidence I have for this assertion is a 13th Century saw found when excavating a midden near Windcliff.

British Push Saw from 1200's found in a midden at Windcliff "Story of the Saw" P.d'A.Jones and E.N.Simons.

It is interesting not only because of it's age, but it appears to be intended to cut on the push stroke, rather than the pull stroke. However it's not a backsaw, but it is a wide blade. Also it is evidently intended to be fitted with a tanged handle.

Moving forward, our next clue, is found in H.C. Mercer's "Ancient Carpenters Tools" pp139 where he says that the tenon saw is first mentioned in the 1549 edition of the "New English Dictionary" and is so thin that it is stiffened with a metal rib. He may have been referring to a saw that is mounted in a metal frame, rather than our moden concept of a backsaw (see MissingLink1) (Thanks to Brian Welch for this insight). The only hand saw images of this time generally depict a sword like two handed saw, with a long thin serrated blade, sometimes curved. The bow saw, frame saw and the pit saw also appear frequently. throughout the medieval period.

The next mention of backsaws appears in J Moxon's 1680's "Mechanick Exercises or The Doctrine of Handy Works" unfortunately he doesn't illustrate the backsaw and his reference appears out of context. As many others have noted, it's a pity Moxon's proof reader missed the oversight. He only shows two saws, one looks more like a serrated long knife, and this one. (actually the page (plate 4) shows 6 saws, including whip-saw, pit-saw, frame-saw and one being sharpened.) Only two candidates for our concept of a back saw however.

A re-reading of the relevant chapters of Moxon, it appears that he was referring to a bow saw with the blade turned at right angles, although why that should make it a "tennant" saw is still unclear. What is clear is that Moxon's proof reader didn't make a mistake, it was just mis-interpreted.

Moxon 1680's "Mechanick Exercises or The Doctrine of Handy Works"

This looks more like a pruning saw, rather than the saw's we are familiar with today. The hand position is actually below the line of the teeth. We now move into the 1700's and still no sign of a backsaw anywhere, but everyone seems to know about them.

The 1736 publication "City and County Purchaser's and Builder's Dictionary" published by Richard Neve mentions the tenon saw or tenant saw as "used for fine stuff, with a back to it; so called from being used to make tenons for Mortises".

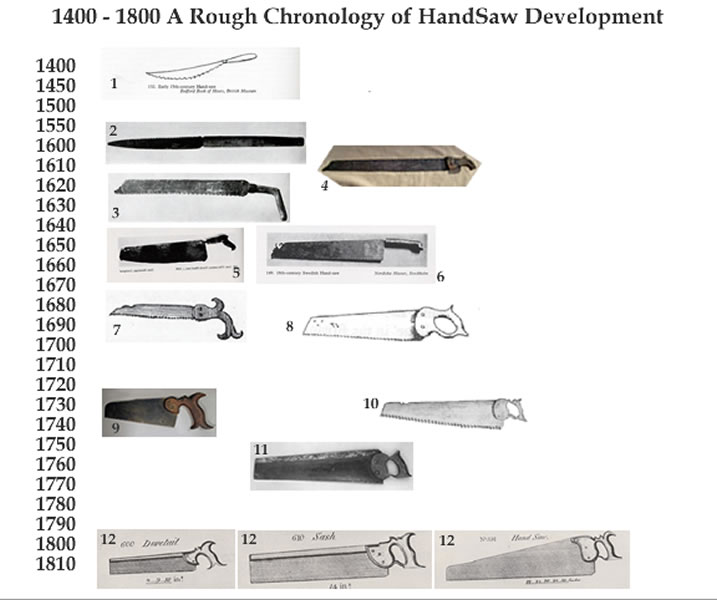

If we take an overview of the period from 1400 to 1800 we can get a sense of the the evolution taking place.

References:-

1.2.3.5.6. Goodman, W.L. "The History of Woodworking Tools" pp 126,pp146.

4 Courtesy Tony Seo (estimated to be circa 1600).

7. Moxon, J . "Mechanick Exercises" London 1683 (Courtesy Mike Wenzloff).

8. Ralamb, A.C. "Skeps Byggerij" [Ship Building] c1691 (Courtesy Don McConnell).

9. Davistown Museum http://www.davistownmuseum.org/toolSaws.html c1750.

10. Trade card of John Jennion London 1732-1757 (Courtesy Don McConnell)

11. John (or Alice) White London mid 18th Century (Courtesy Don McConnell).

12. Smith, J. "Explanation or Key to the Various Manufactures of Sheffield" 1816

By the time Smith's Key was published in 1816, all of the handsaws we are familiar with today had evolved to the forms and functions that we use today. However this evolution appears to have mostly taken place over the period 1700-1800, I suspect that this is a misleading impression we get simply because of the lack of surviving examples. We know that something called a tenon-tennon-tennant-tenant saw was around in the mid 16th Century, we just don't know what it looked like. However we can make some educated guesses that it could have looked a bit like the swedish saws illustrated in 5 or 6 above. Probably with a tanged handle, or it may have looked something a bit like our modern hacksaw. Which "Missing Link 1" was Moxon referring to as a "tennant" saw?

Missing Link Number 1 Circa 1550

(Thanks to Brian Welch for the image on the right: Randle Holme 1688)

We can guess that the change to a rivetted handle possibly occurred around the mid 1600's when commercial saw production began. Changing to rivetting the handle to the blade would have enabled the development of the closed handle. Putting a closed handle on a tanged blade doesn't seem practical . Also the hand position is now clearly above the tooth line. This "Missing Link Number 2" is what I imagine an early 1700's dovetail saw to look like. As yet it hasn't been found. (it might not exist)

Missing Link Number 2 Circa 1700

This example below is from 1750, but the A.C. Ralamb saw pictured in (8) above (1698 or earlier) is very similar to this from, just add a piece of folded steel to the back to the A.C.Ralamb saw and you have the J.Harrison of the 1750's

J Harrison 1750-1770

This J. Harrison and the J. White (11 above) are both steel backed, it appears that larger (early) backed handsaws were generally steel backed and the smaller ones brass backed, the Peter Nicholson writing in the 1832 "Mechanics Companion" , says that the tenon saw has a steel back, and the smaller sash saw has a brass back. I suspect this may have been for cost reasons or perhaps production tooling limitations. Either way the large early backsaws seem to have steel backs rather than brass.

When saw production began in Sheffield, the improved steel production processes led to thinner plate, better quality steel and competition between the various saw makers would have created an environment where improvements in manufacturing technique would have spread rapidly. From 1800 onwards we have many more manufacturers and many more surviving saws to compare. The Sheffield saw industry was well placed to take saw manufacturing to the high art that developed in the years from 1800-1900.

So, when did the first backsaw appear? (apart from the Romans):

The only hard evidence in the form of real saws however, is from the 1750's but we have a description of a tenon saw from 1736 (Richard Neve), which is perhaps a little less ambiguous than Moxon's 1680 reference.

So my answer is a cautious....sometime before 1736....possibly as early as 1700.

I wouldn't be at all surprised to find out it was 1650 however.

That's called having a bet each-way. Further research may help refine the answer.

Ray Gardiner July 2008

Edit 18/10/2008: Fixed link for Davistown Museum

Edit 01/12/2008: Added reference to Richard Neve 1736