Canted Blades (tapered in width)

You can taper the thickness, or you can taper the width, here I am talking about tapered width. Thickness is another matter altogether. You will often see old saws where the blade is decidedly narrower at the toe than the heel. Here is an idea of what I am talking about.

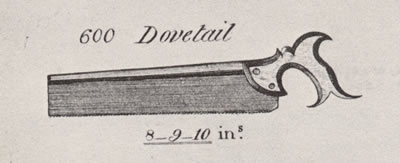

Spear and Jackson Dovetail Saw, showing canted blade

Notice the rather steep angle between the back and the cutting line, some have theorized that this cant has been created by incorrect jointing over many years, some say the back has just slipped and need to bash the brass back down into line. (I have heard stories of tool dealers bashing away at saws to make the blade parallel to the back.) Both theories have some merit, and could cause the same cant (taper). The purpose of this article is to investigate what could cause the canting and why. But before we start, it is a good idea to do some homework and bring everyone up to speed on the state of the discussion.

Joining in the Discussion

For those who are coming late to the party, here is a quick catch-up.

Recently there have been a few articles written on this subject, the first is by Phillip Baker writing in the "Saw Talk" column over at wkfinetools.com http://www.wkfinetools.com/contrib/pBaker/parallelTaper/parallelTaper-1.asp

He concludes, (correctly in my view), that some saws are made with cant (taper), and some made with no canting, but get that way over time.

Chris Schwartz writing in his (always informative) blog over at woodworking-magazine, discusses why having a canted (tapered blade) helps cutting dovetails.

http://www.woodworking-magazine.com/blog/Tapered+Sawblades+Thats+Not+A+Defect+Its+A+Feature.aspx

He also points out that "Smith's Key" a pattern book published in 1816, clearly shows canted (tapered) blades. Thus proving that at least some saws were made with a canted blade.

An alternate view of why smaller saws tend to be more canted is illustrated here:- http://www.disstonianinstitute.com/dovesharp.html

Here Eric Von Sneidern, argues that the canting is induced over time, and repeated jointings because of the difficulty of clamping small saws in a standard saw vise. I am sure that this is a factor, at least in some saws. and should not be discounted.

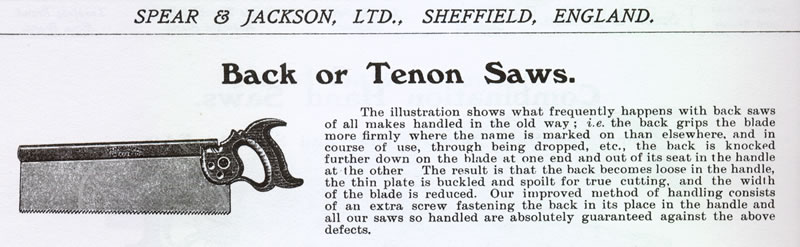

The next contribution to the discussion, comes courtesy Spear and Jackson's 1915 catalogue.

It looks as though my 2 screw Spear and Jackson must be earlier than 1915, I wonder if they can give me an upgrade?

Late Additions:-

The Norse Woodsmith has written a blog on canted blades, you can read it here: http://www.norsewoodsmith.com/blog/1

Now that we are all up to speed on the current state of the discussion, let's take a closer look at that saw we showed above, we will start by dissassembling it, I am going to restore it (eventually) as best I can.

First we look to see if the back has slipped up, and lo and behold, it's about 3/8: higher than the depth of the slot on the handle would indicate.

Looks like Spear and Jackson's 1915 sales pitch was at least partially correct.

It looks pretty grungy, and there is a lot of gunk filling the gap, but the brass back has clearly lifted by 3/8. So let's move on and take the back off.

To remove the brass back, clamp the blade between two blocks of scrap and and then using a block of wood and a mallet, GENTLY tap the brass back

Most of them are not actually that tight as a rule, and come off easily.

Now let's see what we have.

Dissassembled

First off notice that the blade isn't actually tapered at all. It is rectangular. The canting is just an illusion created by the way the blade is assembled into the brass back. and the correct degree of cant is about 1 inch. Ok, so three things we can conclude so far.

1. The brass back had slipped up slightly, increasing the canting.

2. The saw was made with a deliberate cant, that cant being created by inserting the blade at an angle to the back.

3. Repeated sharpenings have not induced any additional canting. (the blade would not be rectangular if it did).

So let's look back a little in time, to see where the canting originated and why it is there. Following Chris Schwartz's lead let's have another look at Smith's Key.

Joseph Smith "Explanation or Key to the Various Manufactories of Sheffield" 1816

Clearly, this is how dovetail saws were intended to be made in 1816, what is not clear is when did the change to parallel backs occurr, If we look at the

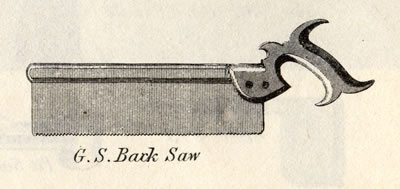

1889 illustrated Trade List of Prices for Sheffield Goods. We see the following.

Illustrated Trade List of Prices of Sheffield Goods 1889

Again, this illustration is intended to show what a dovetail saw should look like.

So sometime between 1816 and 1889 the "standard" changed from canted (tapered) to parallel, no wonder people get confused!. The question as to why it changed I suspect has more to do with the manufacturing processes than with the usability of the saw. Again I should caution against generalizations, this only illustrates part of the picture. We haven't attempted yet to deal with why a canted (tapered) blade would be a desirable feature.

What caused the canting (taper) on my saw?

So If you have a saw with a canted (tapered) blade, is it an artifact caused by repeated incorrect jointing during sharpening?

Well, yes it could be.

The only way to know is to remove the back and see if the blade is rectangular or not. I suspect if you have a post 1900's saw with only a slight cant (taper), say less than 1/4" I would expect that could be caused by incorrect jointing over repeated sharpenings.

On the other hand if you have an 1850's saw with say 1/2" or more of canting and the back is firmly seated in the handle, it probably was made that way.

It may be that earlier saws actually had canted (tapered) blades and the practice of putting the blade in the back at an angle came along later, I would be curious to find out.

What would the advantage of having a canted blade be?

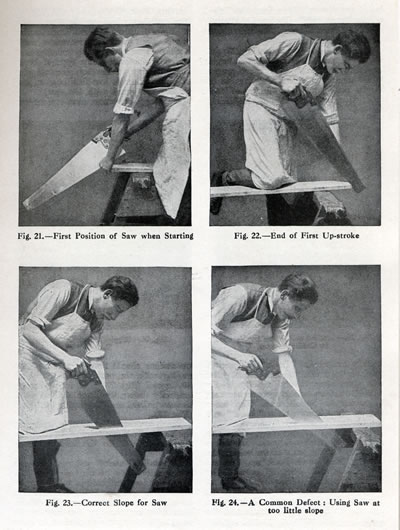

Let's go back to basics and see what the "correct" technique is for ripping a board with a standard panel saw. Notice the angle between the line of the teeth and the board. The starting cut is at a very shallow angle, then moves to a more upright angle.

Using a Rip Saw, "The Practical Woodworker" Bernard E Jones pp 50 Vol 1

"The Art and Practice of Woodworking"

Imagine if you will what happens when the board is vertical, as it usually is when cutting dovetails or tenons, what is the correct angle for sawing?

the angle of the line of teeth will be tilted towards the handle, it is more comfortable to get closer to this angle with a tapered blade. But now we are

at an angle to our desired finish cut, so when we hit the line at the front, simply tilt up slightly for the final strokes.

Why is this angle important (if indeed it is?) well, consider what a rip tooth with zero rake looks like, now imagine that chisel like cutting edge cutting accross a bundle of wood fibres, it is easier to slice at an angle rather than straight down. Cutting at an angle tends to lift the fibres in front of the edge and makes for a cleaner cut with less effort. (I really need to do a drawing to illustrate this..)

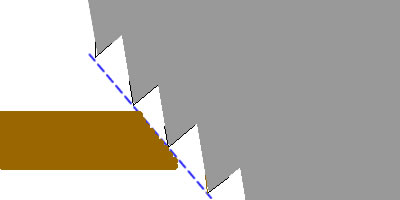

Ripping at an angle (exaggerated)

Here I am trying to illustrate that when you are ripping, the teeth are cutting the bundles of wood fibres at an angle, (imagine a bundle of straws if that helps), now as you cut through this bundle, if you are cutting at a slight angle, then the fibres will tend to lift up in front of the tooth and thus make for an easier and cleaner cut. If you are chopping down at right angles to the fibres, then they won't lift and the excercise becomes a bit like scraping end-grain. I think the above illustration also show there must be some correlation between the cutting line and the rake angle of the teeth.

Something for future study...

Conclusions

So blades are canted because it makes sawing at an angle to the board more comfortable, also makes sawing to a line easier.

There are many reasons why backsaws blades appear canted. From repeated incorrect jointing, back slippage and of course "made that way"

Have a close look at that vintage backsaw with the canted blade and see if you can tell which is true for you.

Addtional Note: I should of course mention that Gramercy backsaws and Mike Wenzloff's Saws are sold with canted blades.

Following a suggestion from Joel Moskowitz (Tools for Working Wood) I have adopted the term "canted/cant" when referring to tapering blade width. Joel informs me that, Tim Corbett - Gramercy Tools originated the term. Thanks Tim, it's the ideal word.

I am not aware of any nomenclature that already covers this, and using "canted" instead of "tapered", removes some confusion from a subject already fraught with more than enough confusion already. Plus, "canted", is a very descriptive and accurate term for this subject.

Ray Gardiner 2008

Edit: RG 4th August 2008: Changed tapered to canted in main text where relevant.

Edit: RG 30th August 2008:Fixing typo's and some spelling. Some instances where tapered / canted were missed.

Edit RG 18th September 2008: Added Link to Leif's Blog.